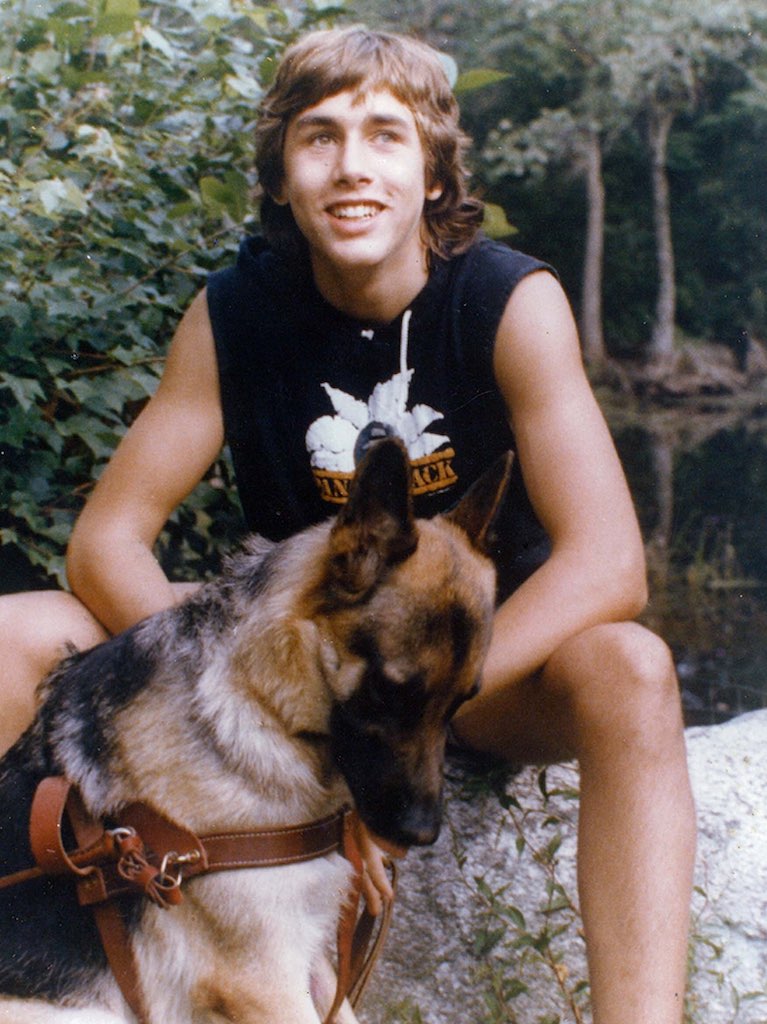

Before Diversity and Inclusion, there was an orange ramp. As I lost the last vestiges of my sight in my early adolescence, the joys of being an adventuresome and rambunctious youth dimmed into darkness as well. In the spirit of Evil Knievel, I loved racing my bike down my driveway and launching myself off a wooden ramp we built at the bottom. However, as my vision slipped away, I was sidelined to the front porch listening to the “whoops” of my friends and brothers as they flew through the air. Witnessing my dejection, my father decided I wasn’t done yet; he found spray paint and coated the ramp a fluorescent orange. That day, I jumped my bike a hundred times, elated by the beacon of hope my dad had created. He could have easily been a barrier or a bystander; instead, he opened a door that I eagerly sped through.

Yet, as I made my way out of my supportive community of family, teachers, and friends, I found the broader world wasn’t as creative or accommodating. In college, I wanted a summer job just like everyone else. Sure, I needed beer money, but more importantly, a first job gave a level of independence, autonomy, and value that often seemed a bit out of reach. I applied for several dishwashing jobs at restaurants, with the idea that I’d washed plenty of dishes at home. The first restaurant manager politely told me that although he’d love to help, their kitchen was too big; he thought I’d get lost and not know where to put things away. I wasn’t convinced that was accurate, but nevertheless, I tried a smaller restaurant where the manager said he’d love to help but their kitchen was too small; I’d bump into things; I’d break the plates. So I tried a medium size restaurant where the manager told me he’d love to help, but the pots were very hot,; I could burn myself, or cut myself on a steak knife. It was a nightmare version of the Three Little Bears, and I learned a brutally hard lesson: despite the level of my skills, my abilities, and my determination, none of these could stack up against people’s perceptions of my limitations. Real and intractable ceilings existed everywhere, made even more apparent by the airplanes in which I was forced to sit in the front row, or the establishments I was kicked out of because of my guide dog, or the opportunities I was held back from by the gatekeepers assuming I was a liability. I had no idea how to break through.

Now, 40 years later, I’m “running down the dream” climbing mountains, kayaking rivers, and leading my nonprofit organization, No Barriers. As my body weakens and I creep towards elder-statesman status, I feel an increasing level of responsibility toward both the general climbing community and the adaptive world. That is, people like me – born or befallen into a category of difference. With the Americans With Disabilities Act and evolving mindsets, a lot has changed – most of it for the better. But despite the progress, I still find myself butting up against walls, although the new walls are more nuanced and slippery. When I looked for a speakers bureau to represent me, I sat with a team at one agency, and they told me, “we already have a blind guy.” I was stunned, but replied, “Well, there’s no rule against having two blind guys on the roster.” It fell on deaf ears.

Preparing for a recent climbing trip to Patagonia, Chile, I sat down to discuss support with a prominent outdoor brand. We gave our well-rehearsed spiel; this trip would be a monumental achievement for many climbers, sighted or otherwise. We would experience rich culture, horrid weather, and stunningly beautiful summits if the granite giants of Torres del Paine decided to grant us passage. A professional photographer was already arranged, and the images from the trip promised to be spectacular. After dutifully hearing us out, they informed us that, unfortunately, the 2022 “diversity” budget had already been spent. I felt the same dull surprise from this all too familiar encounter, and an old wound was gouged open in me. I thought of my mother, who passed unexpectedly shortly after I lost my sight. I was glad she didn’t have to hear about this special budget after spending the first 14 years of my life fighting for my every opportunity and demanding that I had the same rights and privileges as the sighted kids.

Logically, I understand that the existence of special budgets at all is evidence of remarkable societal progress. Through this increasingly empathetic zeitgeist, many disempowered and disenfranchised people are finally finding support and recognition; in the case of the Patagonia trip, things all worked out thanks to the generous sponsorship of Rab Equipment. Yet, a nagging voice within me cries that our society at large can absolutely do better. I was born destined to lose my sight, and somehow the people around me helped me carve a most unusual and fortunate path to the tallest summits on each continent and beyond. This wasn’t due to a special budget or a corporate campaign crafted to check a box or fill a quota. Rather it was a result of a beautiful gift: people who truly saw and understood my humanity, these folks who saw me before I could truly see myself. I wish this path for everyone, “disabled” or otherwise.

When I summited Mt. Everest in 2001, it was compared to “getting a man on the moon.” That’s due in small part to my own efforts, and also, to a huge extent, the efforts of my incredible rope team, from the folks who tied themselves to me at 29,000 feet, to the people back home following progress with bated breath, to the incredibly impressive campaigns by the organizations that believed in me. Our primary sponsor, The National Federation of the Blind, had 100,000 blind volunteers (most of whom were unemployed) conducting bake sales and car washes just to get me to Base Camp. A lot was riding on my efforts, and I didn’t want to let them down.

22 years ago today, on May 25th, 2001, as I crested the summit ridge on Everest, I could sense before me a life of opportunity and adventure. In my mind’s eye appeared my father, my mother, my friends and family and all of the faces I would never know, the faces whose hands and hearts had lifted me to these great and improbable heights. I felt myself part of some broader component of the human experience, unable to yet understand how this tiny island in the sky would change not only my life, but the lives of many who are marginalized and the perceptions of countless more. I could hear the sound of space above and below me, each side of the vertiginous ridge dropping into sheer emptiness, but the last few steps felt familiar and bright, like an orange ramp in the driveway. It felt like coming home.